From Swords to Nukes: Fallout 3 and the Bethesda Open World

Principles of Open-World Game Design, Part 1

Open worlds are all the rage in current game design. So ask yourself. I'm serious, take a minute and ask yourself: what is an open world?

Aren't all worlds open by virtue of them being worlds? And if they aren't, how would an open world compare to a closed one? Is there such a thing as a closed world? In verbal form, what might it mean to open or close worlds? Who coined the term "open world", anyway? Why not "open doors" or "open games"?

Anyone having spent some time playing games in the last decade, or even just reading articles about them, will have an intuitive understanding of the term: there's a big map you can pull up, more or less obvious/explicit markings on said map, most often a quest log separating main and side quests, an expansive 3D rendering allowing traversal in almost any direction; these are the most obvious ones.

There's also a kind of expectation: the notion of the promise. Open worlds promise a certain something, right? Beyond the structures of quests, UI, traversal and character progression, I think the first thing open world game design promises is a feeling. The feeling of immersion, exploration, suspension of disbelief?... Even if, as a word, it’s become so politically loaded, ultimately there is no denying that one fundamental value proposition of open world game design is freedom.

Likely marketing blurb: "In this setting of space and time, with the latest technology available to us, the game will make you feel the greatness, the exhilaration, the excitement and the creativity of freedom. <Epic, endless, saga, gigantic, procedural, etc.>"

But, to understand, to truly go to the heart of the matter, it is insufficient to simply name the facets of freedom, worldly scale, and cutting-edge graphics: surely powerful dimensions (emotion, vision and intellectual breadth), but lopsided & one-dimensional.

Because freedom only goes as far as passivity does: I am free to do what I will, until I start doing it. When I start closing doors of the open world, I'm no longer free because I've made a choice, and I'm bound by that choice to do whatever it is I chose to do. By eating noodles, you deny yourself the eating of potatoes at that moment; by going there, you deny yourself the chance to stay here, and vice versa. Most terrible choice of all: by playing one game, you deny yourself the time to play all the other games!.."

In other words: as soon as I act, the world is no longer as open as it was before my act. Thus do we come to the fundamental problem of open-world game design, and every open world game is an attempt to solve this problem: if playing is an activity, and activity is inherently an act of closing of a world, how can an open world game even be possible?

Fallout 3 & The Start of the Bethesda Formula

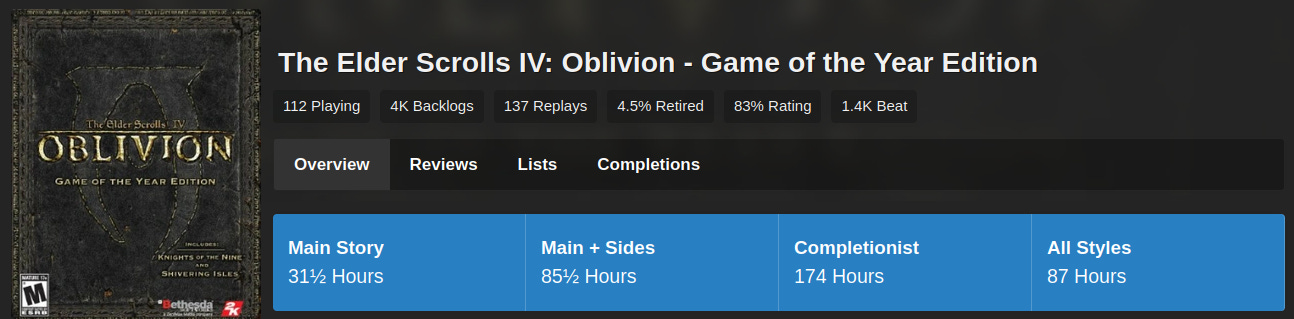

Before Fallout 3 (2008), Bethesda was best known for its Elder Scrolls series: Morrowind (2002) and Oblivion (2006). These were already "open-ended" propositions of the RPG genre itself; but with Fallout, Bethesda went beyond its established IP. As they made Fallout 3, they didn't just copy-paste their Elder Scrolls (TES) formula: they added VATS and the Pip-Boy UI, changed the leveling process, replaced crime with karma, etc. But they also kept a lot of the same things: the closed & unskippable tutorial, the interactivity with objects in the world (same Gamebryo engine that was to become the signature Creation Engine we know of today), the quest design, dialogue choices, factions (guilds from TES). Players even report similar playtime for the "main story" to be around 30 hours.

What, then, is the Bethesda formula for open-world game design? To follow up on the fundamental problem of open-world game design, how does Bethesda go about in solving it? If the logic of open worlds is to define how and when they close, designing open world games has to become an exercise of time and resources to dazzle the imagination and delay the moment of closing. This is what contemplation & immersion stand for: surrogates of that fleeting feeling of freedom. How does Bethesda go about in fostering the feeling of freedom in Fallout 3, and what are the lessons it can teach us about the pleasures and pains of playing an open-world game?

Open World by Closed Introduction

After a pretty uninteresting intro movie (some good images but very poor, generic narrative voice-over) set up as an excuse to trumpet the tired "War never changes" motto, the tutorial section sees you start as a baby and progress towards your adult years, with significant episodes in-between, where you gradually get introduced to the game's mechanics, like interacting with the world in that Bethesda way of "all objects matter", learning to use what was at that point the revolutionary innovation of the Pip-Boy (an in-game, narrative-based UI!) and getting familiar with the combat and character progression mechanics (skills, SPECIAL attributes, etc.).

Speaking of acronyms, which the Fallout lore loves to joke around with, Fallout 3 uses them amongst other devices (voice logs, meaningful collectibles, satirical in-game slogans and text logs) to introduce and immerse you in its lore and world-building. This is what I've come to call the "immersive flavor": it's that special sauce that gives heart and soul to a piece of work, or to meaningful interactions and relationships we foster with others. It's what we mean when we say such and such have personality.

It’s shocking as well as paradoxical that this first section of the game is so successful: you get it, you understand what's going on without too much exposition, stories begin to coalesce, the gameplay is responsive, etc. I cannot stop gushing about UI design in Fallout 3. I was dumbstruck by how clearly and simply the game communicates that you've killed an enemy and accumulated XP: some simple prompts and that sweet, oh-so-dopaminesque cashier sound. This is stellar gameplay reactivity.

But this success is shocking and paradoxical because of two reasons:

1) if you know it's an open-world game and that's what you expect, you might be let down by a 1+ hour long introduction to the game, no matter how good that intro is; after all, you're playing with the expectation, and most likely the desire, to gallivant about the world, eventually to learn about the game at your own pace and in your own way; I've seen more than one Youtuber complain about this kind of problem in the case of Zelda TOTK;

2) but it's especially jarring once you're out of Vault 101, once the tutorial's over and you're thrown outside with the choice of walking in any direction the very visually impressive Capital Wasteland with nary a guiding hand except for the marker of your main quest (the complete opposite of the corridor-like narrative and gameplay that you've been through in the tutorial section).

Open Worlds and the Desert of the Real: When Maps Engender the Lands

"The Desert of the Real" is an expression used, among others, by Slavoj Zizek, by Morpheus from the Matrix, and by Jean Baudrillard in his "Simulacra and Simulation" book, and by Borges in his short story "On Exactitude in Science". This is a very complicated subject for me, that has roots in literature’s modernist turn from the lyrical to the realistic, a subject broached in detail by Roland Barthes when he talks of the "Reality Effect".

I intend to write more on open-world game design, so I'll keep the details of this discussion for another time, while leaving the references here for myself to pick up on and for readers who might want to satisfy their curiosity.

Suffice it to give an excerpt of the original short story:

"In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. [...] In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography." (Excerpt from Borges’ ‘On the Exactitude of Science)

Baudrillard, looking at the world as it appeared to him towards the end of the 20th century, picked up on this short story and wrote:

"It is [now] the map that precedes the territory [...], that engenders the territory; and if one must return to the fable, today it is the territory whose shreds slowly rot across the extent of the map." (Extract from Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation)

To them who would read this post, and to him who has written it, I ask you: are we the beggars/animals of today, endlessly seeking the shelter of the rotting parcels of the real, those relics of a substantive past, for some reason unsatisfied or disillusioned by the maps/societies we are at present invited to live in?

Open Worlds and the Desert of the Real: A Mold of Yourself

It was really important for me to talk about the relationship between open-world game design and this "Desert of the Real" because, beyond the explicit lessons I can take away from Fallout 3's open world, the one (implicit) thing I learned while playing this game, and which struck me so profoundly, is that, at least in Fallout 3's Capital Wasteland open world, you take from it what you put into it.

It was April 18th 2024 when I got out of Vault 101, and I made a point of expressly ignoring the main quest direction and just heading in another (mostly opposite) direction: I found a store with a booby trap and abraxo cleaner box dominoes and I then walked around towards the landmark that turned out to be Tenpenny Tower, looting some blown-up houses/furnishings and shooting some bloatflies on the way over. I got to the Tower and spoke on the intercom, only to be refused entry (I didn't even have the 100 caps to bribe the intercom, having just gotten out of the tutorial). A bit discouraged and bored because nothing much had actually happened on the way over (which contrasted so much with all the meaning and funniness and novelty of the tutorial section), I fast traveled back to the entrance of Vault 101 and decided to follow the main quest after all.

The key of this story is that in real life, I wasn't feeling too jazzy either: I was feeling a bit anxious, bored and somewhat placid before even booting up the game. And the game's open-world structure just threw that back at me, more or less exactly like a mirror. On another day afterwards, I felt more optimistic and upbeat about everything outside of the game; and what a coincidence that it was a joy this time to explore the Capital Wasteland and get lost within the Springvale Elementary school, which had no explicit quest or activity, but whose environmental storytelling was so strong with its object placement and multi-layered level structure (going all the way down to the spider-nest and the story behind why there was tunneling going on below it). The game was expressing the mood I was in before I even started playing.

You might argue that all games are like that; and while that may be true to some extent, it's undeniable and crystal clear to me how different playing Fallout 3 feels compared to, say, an RTS (or even a chess game) match online and the massive adrenaline shot you get with those. So here's one big question, as we go forward in our study of open-world game design:

This mirroring of the self, this power of an open world to mold itself so faithfully to the mood of its player, is it particular to Fallout 3, to Bethesda's own open world formula, or to open-world game design generally, beyond Bethesda's own particular flavour of it?

Time and experimentation will tell.

Open Worlds and the Desert of the Real: Lessons from Fallout 3's Case Study

To finish this week's post, I want to review some of my main takeaways of Fallout 3's open-world mechanics: things that I noticed and wrote down as foundational aspects that give shape to its specific version of what open-world design means.

1. Immersion

+ I've already mentioned UI design, but the Pip-Boy does some major lifting in making the game feel integral to the world it presents: you're not just navigating menus, but menus generated by the game-world itself: peak ludo-narrative consonance.

+ How the game handles item durability and repairs: in another stroke of immersive genius, what you mostly find in the post-apocalyptic wasteland are items in terrible condition, and the only way to repair them is to find the same kind of item from which you can "headcanon" salvage parts in order to proceed with the act of repairing, with the added condition of your repair skill determining how close you can get an item back to mint condition.

+ Ultimately, the biggest contributor to Bethesda-style immersion, as far as Fallout 3 is concerned, is the game engine itself and how it revolves around closed instances filled with interactable, physics-simulating items. These are the items that are there, where and how they're placed and the story they come to tell. I spent a lot of time looking in all the nooks and crannies for hidden items, keys that would unlock boxes, doors or terminals for the simple joy of discovery. In another amazing instance of immersion, I gave serious consideration on which mattress I would sleep inside the Super-Duper Mart in order to regenerate my health: they all did the same job in the same way, but it had become important to me whether I slept next to an urinal, between toilet stalls and how much light came from the ceiling in each case (the Raiders had set up their communal bedroom inside one of the bathrooms, for some reason).

- Even if I recognize its double-edged character, I still think level scaling is largely detrimental FOR the purpose of immersion. Yes, it allows you to go anywhere and in this way let's you truly roam free. BUT it's too big of a risk for the coherence of the game-world itself; the best example I can give about this is low-level me coming out of a metro station as two Brotherhood of Steel soldiers are fighting some Super Mutants: the enemies aren't taking much damage from the paladins because the encounter is designed for you to intervene and act as the deciding factor of the fight, which means my flimsy hunting rifle almost instantly kills the enemies, while the paladin's mini-nukes barely hurt them, which makes absolutely no sense and brutally kills any feeling of immersion, because the Brotherhood, the Super Mutants, all of them suddenly become cardboard accessories instead of effective actors of the game world. Lesson here seems to be that when you offer the player too much choice, when all choices are easy, they stop being meaningful and thus become irrelevant to the tension inherent to the principle of the open-world (the need to make a choice, to close the open world).

2. Quest&Content Design

+ Speaking from experience with some other open world games, I had forgotten just how empty Fallout 3's map initially is, and it felt so refreshing not to have any question marks or "points of interest" already marked on the map. Looking at the map only (and this ties into Borges' story brought up earlier), you might think the world is empty, and this has the interesting effect of "delaying" the moment of choice and thus prolonging that feeling of freedom.

+ This goes so well with the actual types of quests that you come into contact with: there's the tracked&marked main quest along with some of the side quests, but there are a bunch of tracked&unmarked quests (such as the Android looking for doctors quest) as well as untracked quests altogether (fixing the water pipes and bringing scrap metal to Stanley in Megaton). You're not just a train on a railroad, but there's actual exploration required for much of how you interact with the game-world's problems and mysteries.

+ Towns/hubs (like Megaton) make sense insofar as they not only provide a centralized location for various services/vendors (doctors, repairs, equipment, etc.) but they also act like quest hubs sending you in various directions (some more defined than others, horizontal vs vertical navigation). It gave me great pleasure to also notice that their status as a quest hub was all the more eloquent insofar as they also provided their own worldbuilding, with numerous NPCs all having their (hi)stories and problems intertwined within a nexus of meaningful and explicitly constructed mini-locations: the tavern, the water treatment plant, the Church of Atom, etc.

3. Economy

+ Every currency (caps, karma) has not only a useful spending option (currency sink) but also a meaningful one tied into the lore of the game. You need to repair your equipment, get better guns/armor, add conveniences to your house, you can gain followers if you have the karma requirements, etc. This is especially important for a game with item placement/interactibility as a foundational design choice for gameplay AND story.

4. Graphics

+ It's undeniable for anyone following the release cadence of games and especially of open world games that they strive for graphical fidelity more than any other genre: video games are a visual medium after all, but graphics can be striking and well done without using the latest and most impressive rendering techniques; this seems to apply less to open-world games and Fallout 3 is no exception. Even 16 years later, with ray-traced lighting as the new frontier, Fallout 3's pre-baked shading is nothing to scoff at and the overworld vegetation and level of detail streaming distances remain impressive, with only moderate observable pop-in.

- This is less the case with the texture quality: the memory requirements of greater texture resolutions were clearly beyond the tech capacities of the time (no SSDs, console RAM limitations, etc.) and it shows, with textures often being washed out and quite ugly.

~ Art design also seems to go hand-in-hand with the first point on graphics: realism is without a doubt the main aim here, which results in a lot of grey-oriented color palette (it's a post-apocalypse stuck in the 1950s USA metallic aesthetic, after all). It makes sense and does the job, but I can see others qualifying this as simply bland and uninspired.

+ In terms of the actual task of programming, the open-world aspect of data streaming is the thing that attracts me the most: what are the ways to bridge the gap between loaded and unloaded parts/layers of the open world and how can this challenge be tackled not just in an optimizing mindset, but also a game-design mindset? Ultimately, any game is a stream of information being refreshed at a certain interval, and it really bakes my noodle to think about how that is foundational to what kind of a game you're playing in the first place (eg. a game where all data is provided/loaded beforehand, versus data streaming/generation/replacement as a constant process within the act of playing); I think it's an all the more important question in the case of open world design especially.

5. Character progression / Roleplaying

~ Some perks are fun and most of them give some flavor to your character, but they're also mostly generic, quantitative passive bonuses that don't really change anything foundational; their uninspired character is especially telling in the fact that most perks actually have 3 "ranks", each giving 5 extra points to a skill. Skills are mostly the same, influencing success chances of dialogue options and determining whether you meet the thresholds to actually interact with the world (quest items like the Megaton bomb requiring 25 in Explosives, lockpicking/hacking difficulties spaced 25 points apart, etc.).

~ While the game gives you most often binary choices about how to solve a quest, and while you can choose which major faction to align with, most of the gameplay itself revolves around the first-person combat, assisted by VATS insofar as your AP allows. In fact, in my experience the most significant choices in terms of roleplaying are how you treat the NPCs/quest-givers of the game world itself, that is to say whether you kill them or let them live, which links back to combat as a main gameplay mechanic. It makes sense for the Wasteland to be a violent place, but insofar as it does aim for a healthy dose of realism, I would think this to imply people being a bit more cautious and evasive rather than automatically trying to shoot at whatever moves at the horizon.

~ This category also ties into the actual story being told within the larger Fallout narrative/aesthetic, which I am not really interested in judging, for now. It has its place within open world game design, which is what I'm actually interested in, but the very fact of it being an open-world means it largely takes a back seat in order to allow the freedom to do everything other than the main story, which mostly seems to serve as a pretext more than anything.

On the Horizon of Conclusions

That's it for this week.

Next week, I want to start by considering the question of the "Desert of the Real" in more detail, and I want to follow up my study of open world game design by trying out the latest of Bethesda's work: Starfield. It was with Fallout 3 that the Elder Scrolls formula first became the Bethesda formula, and 2023's Starfield, 15 years later, is a great chance to not only see where that formula has been taken by the company, but also what its (relatively) poor reception can say about the state of cutting-edge open-world game design: it's not just a critics versus players thing; it's a controversial game even among players, with a polemical divide between some pilings heaps of praise on it while others denounce it as uninspired and boring. This debate is especially interesting to me, because I’ve often found myself trying universally praised or criticized games and having completely different takeaways (GTA V comes to mind as an example).

If you enjoy this kind of long-form discussion of games and you've appreciated this particular read, consider signing up for the newsletter, kindly delivered to you by email as soon as it's been published. If you prefer the audio format, I also plan on publishing these pieces as a podcast: stay tuned for that! Finally, leave a comment and tell me what you think!