Back towards the beginning of May, I found Dragon’s Dogma 2 (TWO!) at the public library. I had heard of the FIRST game, but never played it. I like trying out different games I’ve never played before (the tantalizing horizon of the new), so I picked it up for my PS5. I think it sat on my window-sill (aka shelf) for a few days before I gave it a spin. (Reminder that physical games media is the best, and also imperiled.)

I kind of skipped the character creator and just jumped in... and I was quite excited? My first notes date from May 8, where I jot down some thoughts about the game’s play on the dragon as a classic villain trope, from the introductory moments. What is the motivation of this dragon to challenge you thus? More broadly, it seemed to me at the time that the game was also asking: “what is a villain”? I liked the fonts and their animation; I actually memorized the Balzac quote because it resonated; and the notion of downplaying socially-accepted reason in a spirit of self-sacrifice was a theme that has stayed with me ever since I read Thoreau’s Walden, last year.

La conviction est la volonté humaine arrivée à sa plus grande puissance.

(Conviction is human will at the moment of its greatest power.)

- Balzac, Le curé de village (1839) (my translation)

Confidence is not conviction

It is with the spirit of that quote and its surrounding meta questioning that I gladly plunged into the game. Plunged, because the game LITERALLY makes you jump of a cliff as a leap of faith into playing it. Leap of faith: this will be just as important.

The two are intertwined for a very good reason: the game is very obscure and difficult to read. Except for the pawn system, which is questionable itself at a meta level (weren’t you, the “Arisen”, chosen from pawns themselves? to command other pawns?? sovereign??), everything around the quest system is the opposite of hand-holding: quest givers are not marked (you have to “find” them), directions/instructions are often vague (“wait a few days”?!?!?) and the story itself is a muddled rigmarole of fetch quests around the concept of a castle intrigue and you being a kind of pseudo-hero, pseudo because you’re often saved by others that are already embedded in the world (the bordello matron, the princely child, the righteous head of guards, etc.).

But it also oozes confidence, and I’m still not sure how to explain it. It comes from a double aspect of 1) having the confidence of 2) trusting the player will be interested.

First the confidence in itself part, before the confidence it puts in the player. DD2 just does all kinds of bizarre (to not say MIGHTY QUESTIONABLE) design decisions:

you can’t choose what you take from chests that are strewn all over the bloody place (instead have to do inventory management);

it tutorializes the most basic mechanics and obscures the most complicated ones (contrary to logic?!);

it force feeds you the pawns which are (possibly!) the only ones that can guide you through a quest you’re stuck in, if they’ve done it before;

it makes you back-track quite a bit and offers no solution (such as mounts) which open world games are very well known to do;

it hides a few of its classes and specializations, and when it does reveal them to you it’s in a most banal way as if it wasn’t a big deal (it is);

it’s full of seemingly interesting mechanics which don’t seem to go anywhere, like reviving NPC’s or their bodies getting to the “morgue”, making counterfeit items which lose all functionality, random monster events that repeat and just give a bit of loot and experience, a very open world in which there is little lore and sense of place;

the list goes on quite a bit... and nothing but a very confident game (developer) would construct such systems in the context of today’s spoon-to-mouth systems & interfaces;

... and so, it is curious what the game expects the player to get out of this, because clearly the player is also trusted to figure out their own fun with this:

is it the question “can I break this” and “what will happen if I do”?

or rather “this world is weird and this makes it interesting because I have no idea what’s going on”?

maybe “there’s ingredients for a fun recipe, I just have to find it”?

By May 21st where my notes on the game continue, I was in my honeymoon with it, and very confident that the game had something to say. I had just started my system hardware course, and what I was learning was (AT FIRST) making me forgive the game’s performance woes, especially in the cities. “As long as they don’t hinder your capacity to play, it shouldn’t matter if it hiccups,” I told myself. I was also very bewitched by the pawns and their often dry and sarcastic remarks, as well as their seeking out forms of understanding (“ah, we’re all of a different vocation”, “ah, we’re all women”). By the 10-ish hour mark, the game kept revealing more and more of its layers, so I decided I would buy the game on PC to support such an effort, seemingly very rare, to build an original experience (physical media be damned).

And that’s where the magic went away. Even though this time I was very eager to fully use the char creator to make a Botvinnik lookalike (1960 World Chess Championship!), when I plunged into the world anew, the immersion failed to hold. All of a sudden, every wart I had been looking over and excusing made itself painfully present to my conscience. Of course, I kept going because I chalked it up to the fact that I was restarting the game and I only had to pass the point where I had switched platforms and the magic would gradually return.

System hardware and its encapsulation: a failure of conviction

Concurrently, I was going deeper and deeper into system hardware. And I was loving that shit so much, it changed how I understood my computer and what it means, as a medium. Finally, I began to understand what it meant to use a computer, and more importantly, to program for one: talk to the silicon. AI is what it is,

But you - at your most frazzled, sleep-deprived, raccoon-eyed best - you can try. You can squint at the layers of abstraction and see through them. Peel back the nice ergonomic type-safe, pure, lazy, immutable syntactic sugar and imagine the mess of assembly the compiler pukes up. […] The machine is real. The silicon is real. The DRAM, the L1, the false sharing, the branch predictor flipping a coin. It’s all real. And if you care, you can work with it. You can make your programs slither through memory like a steel serpent with little to no overhead.

-JJ from deplet.ing

It then became all the more disappointing that the game’s performance did not scale well with better hardware. No matter how good the hardware, there was a problem in the cities and some particular locations. And the more I marveled at the speed of a computer’s functioning as I progressed in the course, the more inexcusable this became, and the more this tarnished what I thought of the rest of the game: instead of trusting its confidence and trying to vibe with its weirdness, I became hostile to it and considered it freakish.

The propagation time for the NAND gates in the 7400 chip is guaranteed to be less than 22 nanoseconds. [...] If you can’t get the feel of a nanosecond, you’re not alone. But if you’re holding this book one foot away from your face, a nanosecond is the time it takes the light to travel from the page to your eyes.

- Petzold, Code: The Hidden Language of Computers, Chap 15

Petzold is referring in to a family of transistor integrated chips. But speeds to caches and registers inside the CPU are (basically) under 10 ns.

Think about that: online games usually show your ping in milliseconds (ms), and if it’s under 100, it’s usually very playable. (myelated) Neurons show a speed similarly measured in ms. With the nanosecond, we’re talking two orders of magnitude faster. Another example of just how fast the computer is: the keyboard hardware.

A [bit] counter repetitively and very quickly cycles through the [...] codes corresponding to the keys. It must be fast enough to cycle through all the codes faster than a person can press and release a key.

- Petzold, Code […], Chap 21

Things are happening at a speed much beyond the human time-scale and, indeed, even human understanding. Zeno’s paradox of infinitely divisible distance was formulated as a challenge to common assumptions: in order to cross the distance between my chair and the door, I must cross half of that distance, half of that half, half of that latter half, and so on, infinitely. The point isn’t, as some mathematicians have done with the limit/calculus, to find a formula which solves the problem, but rather to evoke the radically strange (and inaccessible?) worlds beyond our immediate perception: metaphysics as a postulate of the many worlds within this world; and philosophy an inquiry into the meaning of that possibility.

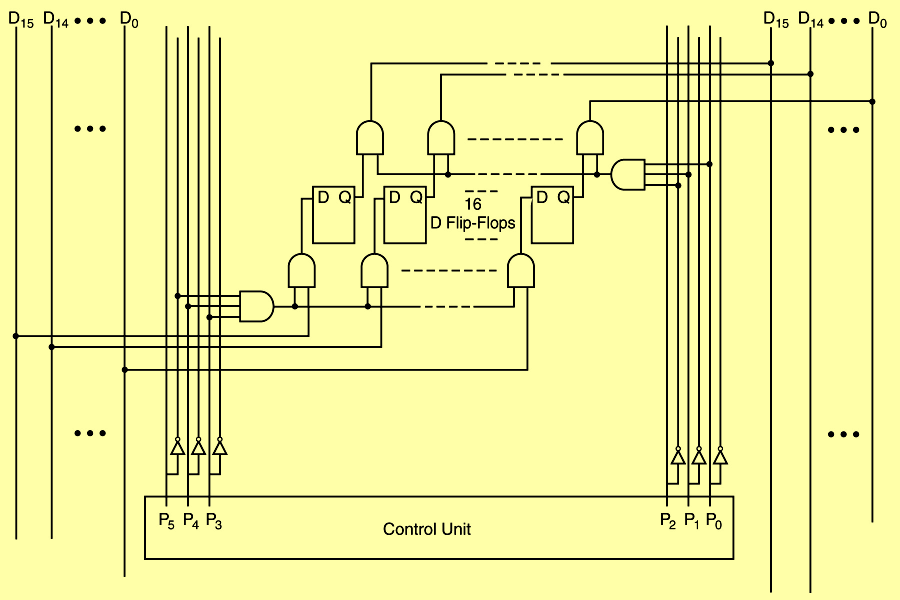

Well, the CPU and the computer as a whole, because of its unimaginable speed, is a very concrete example of that, not to mention the 1/2 becoming 1/4, 1/8, 1/16 etc. is exactly the binary language on which computers function. The CPU is an oscillating device giving out pulses of electricity at rates of billions of times per second (GHz). Instructions must be as small as possible so that each “tick” of the CPU actually does something rather than be wasted waiting for a “longer” task to finish. All of the CPU’s sub-components need to be ready with many preparations in order for the CPU to actually perform its addition: this flows into a notion of synchronicity, some circuits needing to be at the right setting at the right time when the titular clock pulse sends current through those circuits in order to perform the right operation.

This compounding and instantly changing synchronicity IS metaphysical, because we can grasp the basic operation and we most definitely experience its compounding effects every time we use a computer or a “smart”phone, but there is an impossible step to grasp between the initial operations that are at its foundation, and the end-result of playing a game or internet browsing on our phones.

It is impossible to imagine, an encapsulation of electrical symphonic movements, current becoming instantiation destined for immediate destruction. It is fluency by power: every instant of existence confounded into the next by way of a race of billions into logic gates erecting a labyrinthine circuit; certainly countable matter yet also infinitely confounding amplitude.

This is what I took away from my hardware course, and this is the standard to which I held the game I was playing at that time, which happened to be DD2. Woe is me when I played DD2 with all of this in mind: I had to use an inferior peripheral because of controller designed gameplay (condemnable but acceptable), the game takes 40 seconds to start because of Denuvo software protection (when it doesn’t crash at startup because I plugged in the control as it was booting), and most egregiously of all there were significant hiccups and slowdowns in performance despite middling graphics fidelity (definitely unacceptable).

In fact, graphics fidelity doesn’t even matter. Either the game runs well, or it doesn’t. And this one often doesn’t. Because no matter how good it looks, you’re playing a game and you’re doing that on some form of computer (consoles, smartphones: all computers). A game is defined by its dynamism, and computers are the fastest dynamic machine ever invented. (almost) Nothing else runs on the speed of the nanosecond. It is, so to speak, against the nature of the medium to have slower than (almost) instant feedback; sure, you might wait for a very difficult computation to run, and that might take time in areas such as physics, hydraulics or protein folding. But these are games, and as we’ve already discussed in some of our first posts, the reason computer games are immersive and interesting is that they allow a free/cost-less experimentation. And the key to that experimentation is some kind of rapid feedback.

I’ve even experimented playing the game in very pixelated, sub-sampled graphics in order to have zero slowdown and FPS still tanked in the settlements (it was interesting to play like this because I was forced to engage with gameplay and let my imagination do the rest of the work). The developers have previously “blamed” the NPC’s and their concentration in cities as the reason why the game becomes CPU-bound, but this makes zero sense, because there’s nothing interesting about these CPU’s except a seemingly useless affinity system. The most useful NPC is the inn where you can sleep and do storage management, and the vocation guild where you can customize your class and skills. In distinction, NPC’s in Oblivion were notorious for doing weird interactions amongst themselves and displaying some kind of dynamic evolution. Same goes for Stalker’s Shadow of Chernobyl, where factions with different relations had various “unscripted” interactions and the player had to navigate that. None of that is present in DD2. Those were complex NPC systems and those games had no negative performance related to them. It’s a bollocks excuse.

Notice that I haven’t at all talked about the gameplay systems themselves, yet. And “interesting” as they may be, much of that interest is owing to their strangeness. Thus do we come full circle to the leap of faith idea. While initially confident that something would happen, that the game would “pull it off”, the coincidence of a hardware course and the playing of this game made me lose faith in it. In the end, all that strangeness I brushed off as bad design.

And I was wrong.

When we encapsulate virtue

If you’re here because of DD2, bear with me: I need to talk about one more thing: encapsulation. In computer science as it was taught to me at uni, encapsulation is the idea of taking a complex problem and dividing it into smaller pieces: separating and not thinking about that which we are not working on. Software design & programming are VERY labor intensive and complex tasks, so there’s no way one person can think about or understand EVERYTHING that is happening in a program; and they don’t need to.

But the catch!.. is that there is more than one way to encapsulate. Casey Muratori gives a talk about the performance issues arising from a

compile-time

hierarchy of encapsulation

based on the domain model.

What this means is that there is a widespread programming phenomenon, so widespread that it is THE way people are taught to program, whereby instructions for the computer are structured in such a way as to reproduce our way of modelling/interfacing with the world.

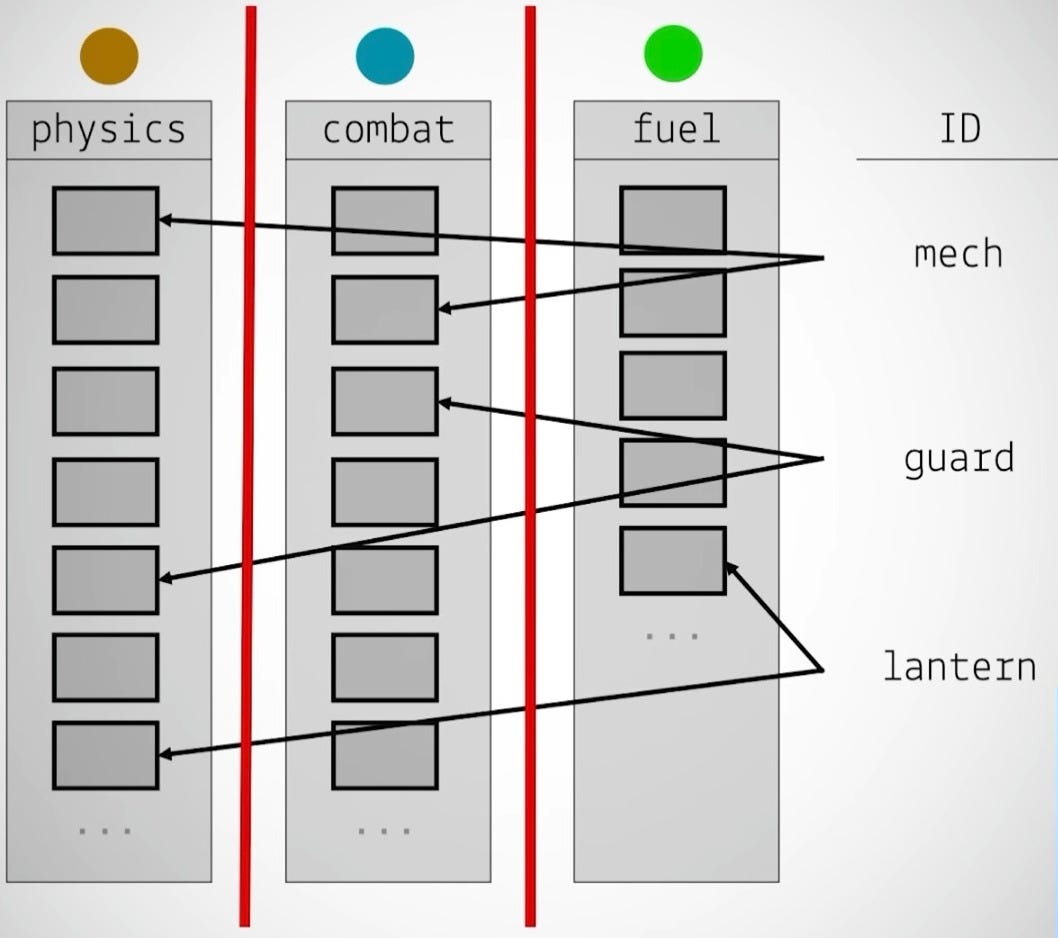

Such programming strategies boil down to creating objects with properties, like an apple and its color. But it just so happens that these strategies result in significantly poorer performance metrics, compared to an encapsulation whose structure rather separates all of the same properties (ie. colors) as their own structure, with objects just pointing towards their correct color, as you can see in the picture above.

And this goes beyond Object Oriented Programming. The more abstraction you introduce in the code, the more “scalable” and “readable” it becomes, and the worse it performs.

There are some mitigating tactics you can employ, such as using increased memory in order to gain some speed (ie. larger hash tables), but these are akin to stapling together some skin and relying on nothing else that it heals properly. The overall strategy remains one of “divide and conquer”, of splitting the project into manageable modules which will have to talk to each other but which are by and large initially independent. Thus, and to repeat myself, encapsulation: each person working on a module doesn’t need to know much about the others. Or do they?

That’s the question at the heart of this post, at the heart of the notion of computer hardware, and at the heart of Dragon’s Dogma 2’s design decisions. How much can you trust the incredibly complex hardware will work. How big is the faith in others in order to go way beyond the possibilities of your individual life/time-scale? How curious do you need to be in order to accept the weirdness of DD2, because its starting moments have given you some conviction in the importance of the experience? Corollary to that, how rapid does the feedback need to be in relation to the measure of trust you are willing to concede?

Seemingly, you have no trouble walking to the door, yet there is a certain infinity of distance between you and it: here surges the moment of metaphysics, where it’s possible to have multiple opposing (and “objective”) interpretations of the same thing (movement is and is not possible, I like and I dislike DD2), which throws a wrench into the nice tidiness of encapsulation and freezes a person’s perspectives of action/praxis.

Kant has a whole section of Pure Reason’s Critique where he presents five issues, each literally having one interpretation/argument on one page (left), and the opposing argument on the opposite page (right); he calls it the antinomies of reason. There is a problematic foundation to human reason, resolvable only in practice and calling for a “solution”:

The solution of the critique, which can be perfectly certain,

does not at all conceive of the question objectively,

but only in relation to the foundations of the knowledge on which it relies on.

- Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, On the antinomies of pure reason, sec. 4 (my translation)

Think about that last quote. Read it one more time.

“The critique does not conceive objectively, but in relation to the foundations it relies on.”

Ask yourself: how does this relate to encapsulation?

--

It’s the opposite of encapsulation. Thinking critically, and finding certainty in that, is only possible by constantly linking the thought to its conditions of possibility, the very opposite of encapsulation, which calls for a process isolated from the rest of its related entities. Programming by talking to the silicon is the process of constantly having in your mind how the actual hardware works, which is counter to the whole point of encapsulation.

More generally, there is a power in encapsulation and the allowance it provides for processes which would otherwise be impossible. But with great power comes great responsibility: that of safeguarding the substantial character of our existence, the meaningfulness which gives us a certainty of and for ourselves. We are responsible for the saving of our soul, and others can only help or hinder us in that endeavor; but they cannot do it for us.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in Emile, lays out the most comprehensive argument I’ve ever met against encapsulation: his thought experiment consists in describing the education of a child which need not rely on the judgment of others; the ultimate non-encapsulation. The discoveries of Emile are his only certainties, the point of the teacher being only to put him in the situations whereby it becomes possible/easier to draw conclusions on his own, or as I would like to put it, for himself (there is a political/virtue angle to this).

While Rousseau never explicitly says it like this (as far as I remember), the argument against relying on an outside authority implicitly involves NOT learning from books because this would involve some measure of trust/faith that the facts or explanations can be taken for granted. As the argument goes, this would render Emile craven and beholden to the power of others in determining his freedom and his happiness.

L’homme vraiment libre est celui qui ne veut que ce qu’il peut,

et qui ne fait donc que ce qu’il lui plaît.

(The truly free man is the one who wants only what he can,

thus one who only does what pleases him.)

– Rousseau, somewhere in “Émile ou de l’éducation” (my translation)

I’ve already mentioned in my Fallout or Starfield posts that open world or sandbox games become what you bring to them: well, I brought encapsulation to DD2.

I had my hints something was going on: I thought maybe cities and NPC’s perform worse because the implicit argument of the game is that cities and society are less interesting & gratifying (ex. scheming regent, boring fetch quests); it’s much more interesting to fight monsters and to face the Dragon, notably because there’s a feeling anything can happen, versus the eternal routine of the cities.

There was a reflection going on here about the Dragon’s status as a kind of endogenous source of virtue & sovereignty. But I ultimately used a kind of

game-time

hierarchy of encapsulation

based on the domain model.

I messed up, relying on the judgment of previous games that I’ve played or seen others play in order to judge this game. I did not sufficiently draw conclusion on my own, because I was busy with other things, or too tired, or too distracted, or unwilling to actually be attentive to what the game was really saying.

What the title menu throws into your eyes as the first thing you see: Dragon’s Dogma, period. Dragon’s Dogma is not Dragon’s Dogma 2. I was ready to drop the game and carry on. But a part of me remained utterly disappointed and I went looking into if and why others would praise the game. And, ironically, through someone else’s video on the game (Punk Duck), I found out that this a deception. There is a Dragon’s Dogma TWO in Dragon’s Dogma 2, and the whole point is to figure that out, to find it.

Ouch.

Now, I return to the game, and I will absolutely come back with at least one more post once I’ve figured out, on my own, what this game means, for me. But this whole voyage of liking DD2, learning system hardware, then also disliking DD2, and figuring out how that is possible through my notes on Kant, Rousseau and encapsulation have brought me to an important lesson I can take with me as I go along my path: conviction is easy to compromise and, somewhat paradoxically, “practical concerns” often weaken the power of praxis to render us unto ourselves as endeavors of meaning. We encapsulate too much, and we encapsulate our conviction, our effort of seeing something for what it is, and through to its end.